The Age of Reason: The 7th Edition of the Festival International du documentaire d'Agadir FIDADOc

Agadir, Morocco, 2015

Sally Shafto

The state of a country’s health can be gauged by its documentaries.

– Reda Benjelloun, Director of the Moroccan TV program, “Des Histoires et des hommes"

If I’m here, it is to acknowledge the work being done by the Fidadoc.

– Sarim Fassi-Fihri, Director of the Centre Cinématographique Marocain

If I am oppressed, you must fight with me for my rights.

– Farraj in I am the People

We cannot imagine democracy without power, in all its forms, being placed in the hands of the people.

–Thomas Sankara

The 7th edition of Agadir’s documentary film festival has just ended and on all levels it was exceptional. Seven is considered the age when children are able to reason and with this seventh edition the FIDADOC has reached a new level of maturity. Besides its location in the pleasant seaside town of Agadir, one of the festival’s principal attractions, to quote its honorary president Nicolas Philibert, is its size: small enough where you can see nearly all the films and meet almost everyone in attendance, and yet large enough for an ample diversity. This year, in addition to a Moroccan panorama and a carte blanche on Swiss documentary, ten feature-length documentaries from the Maghreb and the Mashrek competed.

Fidadoc poster outside the Hôtel de Ville (Photo: S. Shafto)

So rich was the programming that it’s worth saying kudos first and foremost to Hicham Falah, the festival’s Artistic Director who viewed approximately 500 films for the competition. His selection was unabashedly political, and Palestine, the most filmed land in relation to its physical surface, as he observed, was a leitmotif. Programming is not only a form of montage but also, when practiced at the highest level, an art. One of the most intriguing aspects of Hicham’s carefully considered selection was the way the films dialogued between themselves. Falah here follows the example of Luciano Barisone, who since 2010 is the Artistic Director of the highly respected Visions du Réel Festival in Nyon, Switzerland.

Luciano Barisone (Photo S. Shafto)

Barisone was present to introduce his Carte blanche of Swiss documentaries. He grew up in a cinephile family in Genoa and did his initial studies in ethnography focusing on the Caribbean. For many years he worked as a film journalist, first for Rossellini’s Filmcritica, later for the Italian newspapers Il Manifesto and La Stampa. In 1990 he founded the review Panoramiche that became renowned for its in-depth interviews with filmmakers. Before Nyon, he programmed for the festivals of Venice, Locarno, Alba, and Florence.[1]

His conversion to documentary filmmaking, Luciano told us, came relatively late with a screening of Chris Marker’s Le Tombeau d’Alexandre/The Last Bolshevik (1993). Like Rasha Salti, the guest programmer at last year’s FIDADOC, he maintains that the most interesting documentaries display a certain hybridity.[2] But while Rasha speaks about creative documentary, Barisone prefers to discuss documentaries as cinema tout court. In another words: a successful documentary can absolutely have the reach of a fiction film. Nicolas Philibert who has known him since they both were jurors for the 1997 Caméra d’or at Cannes, paid him warm tribute:

Luciano doesn’t make films. But for me he’s a filmmaker. He speaks like one. In addition, his regard is always benevolent. Everything interests him. He is a man of dialogue who creates links between films. He knows how to creates dialogue between them.

Certainly one of the principal considerations in documentary is the relation of filmer to filmed. In this year’s line-up it was fascinating to see how often filmer and filmed spoke directly to each other. And insofar as the filmer is a stand in for the spectator, also to us. In the Egyptian documentary I am the People, the subject, Farraj who is illiterate does not mince his words saying: “If I am oppressed, you must fight with me for my rights.”

In my review of last year’s FIDADOC, I noted that British filmmaker Deborah Perkin (Bastards) subscribes to the fly-on-the wall, observational school of documentary filmmaking also known as Direct Cinema, where the fourth wall is never broken. Philibert, on the other hand, suggests that striving for such objectivity is inherently futile. If you ask ten different directors to make a documentary on the same subject, he reminded us, you will have ten different films in the end. Today, many increasingly realize the porous nature between documentary and fiction.

The FIDADOC is not just a venue for screening documentaries, it is also a catalyst for Moroccan documentary film production, called “La Ruche documentaire” (the Documentary Beehive). According to Lucas Rosant, the author of an EU report, Morocco lags behind other Arab countries in co-productions of documentaries.[3] But what’s particularly interesting about the Moroccan example is that filmmakers here don’t feel constrained to specialize in fiction or documentary. They can move fluidly from one to the other, as Nabil Ayouch (Ali Zaoui and Promised Land) and Leïla Kilani (Our Forbidden Places and On the Edge) have both adroitly done, or as the French director, Barbet Schroeder, has done over his long career. When a fiction film can take years to finish, it makes sense for directors to try their hand at documentary. Since October 2012 documentaries are able to compete with fiction films for the Moroccan government subsidies, Avances sur recettes. Sarim Fassi-Fihri, the new head of the Centre Cinématographique Marocain, who was present for a closing panel on Saturday morning, noted that he would be content with two good documentaries a year.

For Reda Benjelloun, the “Ruche documentaire” is already producing its honey. During the week of the festival the young authors of twelve selected film projects conferred with experts on their projects in development. The role of the Moroccan TV channel 2M that hosts Benjelloun’s popular documentary film program (entitled “Des Histoires et des hommes”) is crucial. In the Maghreb and the Mashrek, where illiteracy remains high, the impact of television is enormous. In watching I the documentary, I am the People, I was startled when an Egyptian villager confides to us that television is synonymous with joy! In the past when someone died, he added “the television would be turned off for a year,” as a sign of mourning and respect.

For Benjelloun “documentaries offer a litmus test for a country’s health.” In the Moroccan audiovisual landscape, where the public remains very attached to highly formatted foreign soap operas, it would be hard to overestimate the importance of his television program that airs on Sunday evenings: “Des Histoires et des hommes” offers its audience a window onto the world. Films like Deborah Perkins’ documentary on single mothers in Morocco (Bastards) that was shown there last year are slowly helping to transform Moroccan society. In this context, it is worth acknowledging that King Mohamed VI has just changed the law, making abortion, in certain instances legal. In a country where hundreds of clandestine abortions continue to be practiced every day, this is clearly a major advance.[4]

Similarly, Raja Saddiki’s documentary Aji-bi, Femmes de l’horloge, co-produced by the Moroccan television channel 2M and Nabil Ayouch’s production company Ali n’ Productions, will contribute to increased understanding of the plight of Subsaharan Africans in Morocco. Many of them come here as a temporary holding place hoping to settle in Europe. Denouncing the quotidian racism they confront, her documentary highlights a new kind of immigration where young women abandon family and children back home to find work in Morocco. Saddiki focuses on a group of Senegalese women working as unofficial hairdressers in a certain neighborhood in Casablanca, near the large clock in the old medina. One of them remarks that Moroccans who address them as Africans often seem to think of themselves as Europeans! In her q and a with the public Rajja told us that she became intrigued with this group of immigrants whom she saw everyday while walking to work. On a more positive note, the film points to Morocco’s increasingly more understanding attitude towards these residents, many of whom have now been given papers by the government.

I am the People

One remarkable film this year was the aforementioned Egyptian entry I am the People. Its filmmaker, Anna Roussillon, Lebanese by nationality grew up in Egypt, and today teaches Arabic in Lyon, France. Roussillon offers a portrait of Egypt in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. Interestingly, she chose to film not in Cairo but in the countryside near Luxor, a region that has suffered greatly in recent years with the precipitous decline in tourism. Her Everyman, Farraj Jalal, observes that despite the 2011 revolution that ended the thirty-year presidency of Hosni Mubarak, nothing has changed for the Egyptian people.

Roussillon began filming in the summer of 2011. She captures the incredible wave of enthusiasm that took hold of the country during the 2012 election, where for the first time women too were allowed to vote. With Mohamed Morsi whose campaign slogan was “Vote for Morsi and you’ll go to Paradise,” Egyptians were governed for the first time by a civil, non-military person. Farraj confides: “For the first time I feel that my vote carries weight.” To which Morsi in the televisual reverse shot replies: “You are the source of power and legitimacy.” But one year later, in refusing anticipated elections to his people many of whom could not even afford a bottle of gas, Mohamed Morsi offers the filmmaker an incredible morality tale, as well as narrative arc for her documentary. It’s worth nothing that Roussillon did not know her subjects before beginning her film. Over the course of her three-year shoot however a friendship clearly developed between them, so much so that Farraj encourages her to be buried in Egypt so that they may remain close.

Opening Shot of La Route du Pain

This year’s festival also included a sidebar of Moroccan documentaries, where La Route du pain (66 minutes) by Hicham Elladaqui, a graduate of ESAV – Marrakech, was a personal favorite. If thematically the film is similar to that of I am the People, it’s worth emphasizing that Elladaqui’s documentary shone in this year’s line up for its exceptional filmmaking. From its opening languorous plan sequence, the first of many, I knew I would like it. Unlike Anna Roussillon, Elladiqui was already intimately acquainted with his subjects before filming began. They are his neighbors in Marrakech. Early on, one of the interviewees proffers some advice, which is repeated like a refrain: “You have to have two jobs. If one doesn’t work, you can always fall back on the other.” Despite the terrible poverty that threatens them where a family can afford neither a clean shirt nor even a new notebook for their child, these individuals maintain their dignity. They are aided precisely by Elladaqui’s manner of framing, where a subject is filmed in corporal entirety in her or his environment. This is filmmaking on a human scale that echoes the work of the Italian Renaissance master Piero della Francesca where bodies have real substance. “La route du pain” whose title resonates with Mohamed Choukri’s classic autobiography Le pain nu (By Bread Alone in Paul Bowles’ translation) for many in Morocco remains difficult. In the film one person observes that “There is no one to help you. We are lost in our own country.” The contrast between the daily lot of Hicham’s neighbors and the other Marrakech, seen briefly at the end of the film, of sumptuous hotels and riads, borders on the obscene.

The Swiss Panorama included two films by the well-know documentarian Francis Reusser, both on Palestine. I was particularly fascinated by the first one, Biladi, une revolution (My Country, a Revolution; 1971), which Reusser rightly describes as a film tract, caught up in an idealization of the PLO. Reusser shot the film at the same time that Godard and Gorin filmed “Jusqu’à la victoire.” Uneasy about being used as a political tool, Godard shelved it. Several years later with the collaboration of Anne-Marie Miéville, who also participated in the Reusser film, he released it as Ici et ailleurs (1976).

President Thomas Sankara surrounded by Artists Miriam Makeba, Tshala Muana, Georges Ouédraogo, Nayanka Bell, Nahawa Doumbia, Fespaco 1985. Photo © Brigitte Katharina Franzke-Sodatonou

The poster for the film Captain Thomas Sankara

One theme that stood out this year was that of brothers, either literal or figurative. In the Helvetic selection Christophe Cupelin’s biographical documentary Captain Thomas Sankara, about the charismatic former president of Burkina Faso and one of the most important African leaders of the last century, triumphed. A military man by default who received his political education during the uprising in Madagascar in 1972, Sankara led his country for a scant four years (August 4, 1983 – October 15, 1987). He was like a shooting star that illuminated Africa still emerging from neo-colonialism and la Françafrique. The brevity of his governance belies the profound changes he engendered at home. With a 98% illiteracy rate and deep-seated corruption, he had a lot to do.

Cupelin has fashioned an intensely satisfying survey of this incredible, larger-than-life revolutionary figure out of carefully selected archival videos, radio interviews, and still photographs. The result, reminiscent of Chris Marker, is very moving. Excerpts from Sankara’s many speeches reveal him to have been a talented orator with a gift for salient repartees. On July 29, 1987, Sankara addressed his African peers in a conference in Ethiopia on the topic of the outstanding African debt to the IMF:

The debt can’t be paid back. The debt cannot be paid back, firstly because if we don’t pay, our debtors won’t starve to death. You can be sure of that. But if pay, we will starve to death. Be sure of that as well. [. . .] For the rich and the poor, morality means different things. [. . .] We need two editions of the Bible and two of the Koran.

The film’s parti pris is one the filmmaker, who visited Burkina Faso twice during Sankara’s presidency, fully assumes. It’s certainly hard not to fall under the charm of this frankly astonishing political leader who renamed his country “Burkina Faso.” Meaning the Land of Honest People, Burkina Faso replaced its former colonialist geographic, but otherwise meaningless designation as Upper Volta.

As a political filmmaker, Godard occasionally disconnected the sound and image tracks to sharpen our vision and hearing. As a statesman, Sankara, understood the equal value of words and actions, but more importantly, that the two need absolutely to be in synch. Legendary for his probity, he received a monthly salary of a mere 230 € in today’s money. Sankara fought the good fight: he struggled against the alarming illiteracy rate, he advocated vaccinating Burkinabé children, and for equal pay for Burkinabé women. In addition, he was focused on protecting the environment.

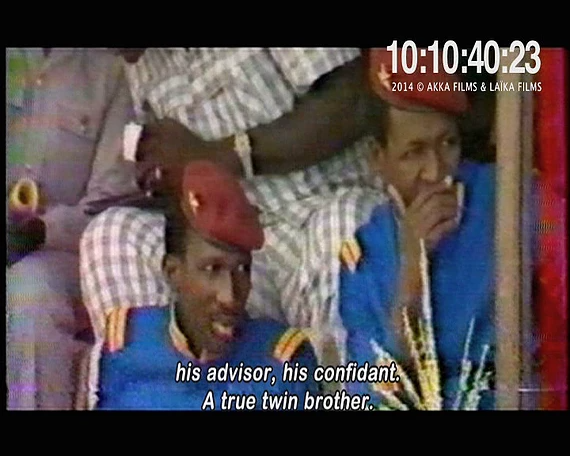

Sankara with Blaise Compaoré behind him

The opening, proleptic scene where Sankara, delivering his presidential speech to his people, brandishes his magazine of bullets to be used against imperialism augurs the coup d’état that would topple him. His assassination remains unelucidated, but he was probably murdered by his best friend and his homme de l’ombre, Blaise Compaoré (the two men first met here in Morocco in 1976 during a military training in Rabat). Sankara was no dupe: in one interview he reflects on his relationship to Compaoré who was like a brother to him. With the recent fall of Compaoré’s regime, Burkina Faso is currently undertaking the work of bringing to light–nearly three decades later–the circumstances of Sankara’s death. Thomas Sankara may be dead, but this documentary has succeeded in bringing him back to life. In so doing, it will aid his people to properly mourn him.

Sankara’s importance and his political relevance, however, isn’t restricted to his small country of 17 million. He recognized apartheid as the modern-day form of imperialism. Captain Thomas Sankara deserves a wide showing in the United States, where the struggle to better integrate young black men–as recent events sadly attest–is long overdue.

In Captain Thomas Sankara Blaise Compaoré remains a shadowy presence occasionally seen in the background but never heard. In Sandra Madri's Saken another pair of metaphorical brothers occupy the storyline, this time with emphasis on them both.

Ibrahim in Saken

It’s a documentary about the former elite Palestinian Fedayin soldier, Ibrahim. He participated in the offensive against the Israeli army in southern Lebanon in the early 1980s. Assigned to a mission meant to protect the passage of Yasser Arafat (who ultimately took a different route), he was shot in the neck by a sniper and subsequently paralyzed for life. When we meet him he has been confined to a hospital bed in a Palestinian military hospital in Amman for years. Despite his condition, Ibrahim lacks neither humor nor humanity. He is cared for by an Egyptian nurse, Walid, who has come to Jordan for work, but ends up being separated for months at a time from his family.

As the narrative unfolds, the attachment of these two men becomes clear. Ibrahim asks Walid if his body frightens him. Walid responds that he is just concerned about hurting him because his body, once so powerful, is now so fragile. Without Walid, Ibrahim literally cannot live. When his caregiver decides to return to Cairo for an extended visit, Ibrahim dies. Little by little, in the huis clos of Ibrahim’s hospital room, we come to understand that Saken is a love story between these two men who are like brothers. The title “Saken” means both “he lives” in dialectical Arabic, and “he’s stuck” in classical Arabic. It’s hard not to agree with Hicham Falah’s assessment that Saken is a masterpiece.

Trêve

In Myriam El Hajj’s Trêve/Truce, we meet another pair of brothers, this time real siblings. In I am the People, filmmaker Anna Roussillon is heard but is not seen. Similarly, in Saken the filmmaker occasionally poses a question but is not seen. In contrast, in Trêve Myriam El Hajj despite her initiation hesitation is physically present in the narrative. Trêve’s subtitle (“A Time for Rest”) could be changed, in reference to a film by Agnès Varda (L’Une chante, l’autre pas, 1977): “One Talks, the Other Doesn’t.” El Hajj’s film is a courageous exploration of her own coming to terms with a taboo past, a past that her uncle (Tonton Riad) is willing to talk about, but that her father eludes. It was only when she arrived in France, the filmmaker told us, that she began to question the role of certain male family members in the Lebanese Civil War. In the Sabra and Shatila massacre that occurred in September 1982 a large number of Palestinian refugees were killed by the Phalangists or extreme right-wing Lebanese Christian militia, with the complicity of the Israeli army.[5] This history is recounted, from an Israeli point of view, in Ari Folman’s animated award-winning but also controversial documentary Waltz with Bashir (2008), whose title refers to the Phalangist leader, Bashir Gemayel. In Trêve El Hajj makes reference to the so-called Kissinger plan whereby the Middle East would be evacuated of its Christians, despite the fact that the Christian population in the region dates back to antiquity.

In his remarks Luciano Barisone reminded us how important the first images of a film are, and those in Trêve, where we watch rifle cartridges being assembled in a factory, sets both the tone and the rhythm for what’s to come. Subsequently, we meet Tonton Riad in his weapons and ammunitions store that is a hangout for his buddies. With them and sometimes alone, he nostalgically reminisces about the war, which for him is just part of life. He even tries to teach his niece how to shoot a firearm.

El Hajj studied filmmaking at Paris 8 and the film is dedicated to her mentor and friend, Jean-Henri Roger. In the q and a, Hamid Aïdouni, Director of the Master in Documentary Filmmaking in Tetouan, observed that Lebanon lacks a national textbook, because the country’s identity is too pluralistic for just one. Watching the film brought Jean Renoir to my mind, in part because of the hunting scenes. But also because of Renoir’s famous phrase (as Octave in La Règle du Jeu) of moral murkiness: “Everyone has his reasons.” In reviewing her forty hours of rushes, El Hajj quickly realized that everything revolved about this past war. Or in the words of historian Henri Rousso, writing about France’s Vichy past: “C’est un passé qui ne passe pas.” Trêve is a powerful first film.

Screenings for this year’s FIDADOC were comfortably held again in the auditorium of the Hôtel de ville, since Agadir is still sans cinema. In his documentary Bla cinema (literally, “Without Cinema”) the Algerian filmmaker Amine Ammar-Khodja discusses the transformation of the former Hollywood cinema in the Meissonier neighborhood of Alger. Practicing cinéma vérité, he queries persons on the street about cinema. One audience member described the film as an example of doing “micro trottoir” (street interviews). Not surprisingly, since his sample population is made up of street persons or persons of extremely low income, cinema is of little interest to them.

Ironically, one of the only buildings not to crumble in Agadir’s devastating earthquake, which lasted just fifteen seconds on February 29, 1960, was the Salem Cinema. Today, it remains closed and in disrepair. Perhaps a crowd-funding project could be initiated to restore it as part of Agadir’s patrimony? Particularly moving in the closing ceremony was the short film from INA’s archives of Agadir in the immediate post-earthquake period.

Agadir post earthquake

In the closing panel discussion. Virginie Linhart, a documentary filmmaker and Vice President at SCAM (Société Civile des Auteurs Multimédias) in Paris, noted that a documentary offers a reflection on reality and in filming reality it also transforms it. Documentaries, she reminded us, have the distinct merit of helping us to think differently, thus to live differently. Linhart also emphasized the importance of gender equality in the audiovisual domain where women remain under-represented and she paid homage to Julie Bertuccelli who is the first woman to preside SCAM. While the ACLU is currently threatening Hollywood for its pernicious sexism[6] and Cannes continues to beat its breast in its ongoing but ineffectual efforts to find sufficient films by female filmmakers for its main competition (just 2 out of 19 this year), the FIDADOC can be proud of its near parity: 4 out of the 10 films in the main competition were by women. And the news gets better: of the five prizes awarded, four were won by women. Likewise, in the Ruche Documentaire, of the seven projects retained, six are by women.

(Comparatively speaking, Morocco’s record is surprisingly good on this score: in the 16 editions of its national film festival, a female director has four times won, including this past February when Tala Hadid, a graduate of Columbia University’s School of the Arts, won the Grand prix for The Narrow Frame of Midnight, which was just shown at the New York African Film Festival. Not quite parity, but much better than either Hollywood or France.)

It’s worth nothing that this year’s FIDADOC jury was made up of three women (the Spanish Director of the Barcelona Festival of Arab and Mediterranean Cinema, Meritxell Bragulat Vallverdu; the Egyptian Director and Producer Marianne Khoury; the Malgache Director and Producer Marie-Clémence Andriamonta Paes). I was particularly pleased to meet the male juror, Karim Boukhari, whose work I admired as the former editor-in-chief of the Moroccan magazine Tel Quel.

From Left to Right: Reda Benjelloun, Hicham Falah, Sarim Fassi-Fihri, and Hind Saïh. (Photo: S. Shafto)

In his final remarks Nicolas Philibert reminded us that for a long time documentary filmmaking was regarded as a sub-genre (sous espèce), the poor kin of fiction films. As a young filmmaker, in private screenings of his films for his family, one uncle would invariably say: “It’s wonderful Nicolas, but when are you going to make a real movie for us?” Since then, documentaries have come a very long way. For Hicham Falah, no fiction can procure the emotion of a well-crafted documentary. Philibert usefully reminded us of the recent strides made by documentary films on the international festival circuit. Last year Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Look of Silence won the Grand Prix at the Venice Film Festival, while at the 2014 Berlin Film Festival, the Silver Bear for Best Screenplay went to Patricio Guzman’s El Boton de Nacar, not to mention Michael Moore’s winning of the 2004 Palme d’Or for Fahrenheit 9/11. Last year 102 documentaries were distributed in France, 70% of which were French. Clearly, documentary is no longer the hapless brother of fiction films. It too has reached the age of reason.

Official Jury Prizes:

•Grand Prix: Anna Roussillon’s I am the People (France & Egypt, 2014/ 111’) •Special Jury Prize: Myriam El Hajj’s Trêve (Lebanon & France, 2015/67’) •Human Rights Prize: Sandra Madi’s Saken (Jordan & Palestine, 2014, 90’) •Audience Prize: Raja Saddiki’s Aji-bi, Femmes de l’horloge (Morocco/66’) •2M Prize: Lamine Ammar-Khodja’s Bla Cinéma (Algeria & France, 2015/ 66’) For more on this year’s FIDADOC, please consult its website: http://www.fidadoc.org/category/fidadoc-2015

[1] Muriel Del Don, “Luciano Barisone, Artistic Director, Visions du Réel,”

http://www.cineuropa.org/it.aspx?t=interview&l=en&did=289835

[2] See Rasha Salti’s remarks in my review of last year’s Fidadoc:

http://www.frameworknow.com/#!In-a-State-of-Grace/c1ny0/8AC42D92-375C-4AD5-B0F0-622EEC8BDBE2

[3] Lucas Rosant, “Census and Analysis of Film and Audiovisual Co-Production in the South-Mediterranean Region,” (Euromed Audiovisual III Programme: 2013).

[4] Associated Press, “Morocco King Eases Restrictions on Abortion for Incest, Rape,” New York Times, 16 May 2015: http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2015/05/16/world/middleeast/ap-ml-morocco-abortion.html?_r=0,

[5] http://blogs.mediapart.fr/blog/raoul-marc-jennar/170912/sabra-et-chatila-il-y-trente-ans-1

[6] Hollywood Sexism is Ingrained and Should be Investigated, ACLU says,” The Guardian, 12 May 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/may/12/hollywood-sexism-female-directors-aclu-federal-state-investigation